Hidden beneath the oak-beamed roof of St Thomas' church in historic Southwark, you will find a 300 year-old garret once used by St Thomas' apothecary for the storage and curing of the herbs that were used for medicinal purposes.

Some wards of St Thomas' hospital were built around this baroque church - and connected to the garret itself is the Old Operating Theatre; the only such theatre to survive from the 19th century, complete with its wooden operating table and also the observation stands from which spectators and medical students could witness the surgeries being performed.

It was in this unique historical venue that The VV presented the following talk entitled: Drugs, Blood and Human Skulls - with some truly haunting music provided by Kirsten Morrison.

While you were in the Herb Garret earlier on tonight, while surrounded by hanging skeletons, and those instruments of torture once used as a matter of course in the treatment of many ailments – whether cupping, or bleeding, or trepanning – which is boring holes into human skulls – and more of skulls later on ...well, perhaps you also chanced to stand beneath one of the attic rafters, where, back in 1821, the dried heads of opium poppies were found – just one of the herbal ingredients in common use for centuries to alleviate pain of the body, or mind.

When it comes to Victorian London, and drugs, we often think of opium dens - those fetid, fuggy Limehouse shacks in narrow alleys by the docks where Chinese dealers supplied addicts with pipes. Chasing the dragon. Lost in dreams.

But, such scenes were never that common in real Victorian life, more likely to be found within Sensation novels of the time. Or, as in Charles Dickens’ Edwin Drood - a powerful condemnation of the evils of addiction, when at the very start we see a character who is: "Shaking from head to foot, the man whose scattered consciousness has thus fantastically pieced itself together, at length rises, supports his trembling frame upon his arms, and looks around."

He wouldn’t have to look too far for his daily dose of opium. Victorian England was awash with the drug – and yes, opium did come from China, but the poppy was also processed into resin in Indian factories before ending up upon the shelves of every English pharmacy – and mostly ingested though powders or potions, and often leading to overdose, with many children lost while doped with supposedly innocent tinctures of cough medicine, or teething drops.

Mrs Winslow had much to answer for, with advertisements which offered:

ADVICE TO MOTHERS!—Are you broken in your rest by a sick child? Go at once to a chemist and get a bottle of MRS. WINSLOW’S SOOTHING SYRUP. It is perfectly harmless and pleasant to taste, it produces natural quiet sleep so that the little cherub awakes “as bright as a button.” It soothes the child, it softens the gums, allays all pain, regulates the bowels, and is the best known remedy for dysentery and diarrhoea. Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup is sold by Medicine dealers everywhere at 1s. 11⁄2d. per bottle. Manufactured in New York and at 498, Oxford- street, London.

First marketed in 1864, one fluid ounce of this soothing syrup contained 65 grams of morphine! No wonder the child on the left of this advert appears to be in a comatose state – not knowing what it wants the most – mother’s milk, or Winslow’s syrup!

Among the adult offerings there was Gee’s Linctus, or Collis Brown’s Chlorodyne, and for more recreational pursuits ‘confections’ were packaged like boxes of chocolates, with individual twists of powders sweetened with sugar or syrup. They do look quite appealing!

But perhaps the most popular potion to sit in Victorian medicine chests, or to lie close at hand on bedside stands, were the ladylike bottles of laudanum, which even Queen Victoria used for headaches and her menstrual cramps. A potent narcotic it was as well, containing all opium alkaloids, including morphine and codeine.

But perhaps the most popular potion to sit in Victorian medicine chests, or to lie close at hand on bedside stands, were the ladylike bottles of laudanum, which even Queen Victoria used for headaches and her menstrual cramps. A potent narcotic it was as well, containing all opium alkaloids, including morphine and codeine.

Ophelia by Millais - the painting is owned by Tate Britain.

The beautiful Lizzie Siddal, the Pre-Raphaelite model who married Rossetti (and in the image above she is shown when she posed for the tragic role of Shakespeare's Ophelia for a painting created by Millais) was hopelessly addicted. And her own sad fate may well have inspired her sister in law, Christina Rosetti, to write the disturbing poem known as Goblin Market - a subversive, so called fairy tale which is full of longing for sex, and drugs, and in which another Lizzie is seduced by the juice that the goblins sell – those goblins like devils come from Hell: ‘Their fruits like honey to the throat, But as a poison to the blood.’

Goblin Market - illustration by Arthur Rackham

That poison may have been the cause of the stillbirth of Lizzie Siddal's daughter. The next child she conceived was never born, when Lizzie slipped into a coma one night, following an overdose... after which Rossetti painted his wife with a poppy flower in her hands; the source of the drug that killed her.

And at this point I'd like to introduce a truly haunting, mournful song called GONE, from a poem by Lizzie Siddal, and with music composed and the words then sung by the talented Kirsten Morrison -

Beatra Betrix by Rossetti

And at this point I'd like to introduce a truly haunting, mournful song called GONE, from a poem by Lizzie Siddal, and with music composed and the words then sung by the talented Kirsten Morrison -

A sweetly touching, poignant song for a life with such a bitter end – after which something quite ghoulish occurred, because at the time of her burial in London’s Highgate Cemetery, Rossetti melodramatically wound a book of his poems through Lizzie's hair, and there it remained for seven years, until, when in need of money, and in something of an artistic rut, he returned to the grave at the dead of night, dug up the coffin, untangled the book, and was said to be shocked to see the corpse, and the way his wife’s lustrous red locks had continued to grow so much in death – almost appearing as Undead – a character from a vampire tale inspired by the use of Opium – when subconscious imaginations might conjure lurid fantasies.

Dreams of blood. Dreams of death. And, drugs inspired many Victorian writers; writers like Bram Stoker, who may well have suffered dreadful dreams after seeing this Crusader’s mummified corpse in the crypt of St Michin’s Dublin church; a corpse which almost looks as if some blood might bring it back to life again – despite having met its end getting on for a thousand years before. And when writing his novel, Dracula, the middle aged Stoker may well have known that his own death was then close at hand - because of the blight of syphilis.

With no antibiotics to cure the contagion, the Victorians only had Mercury – the side affects of which could be as vile as the disease itself – with ulcers, hair loss, headaches, weight loss, fatigue, disfigurement, paralysis, blindness, madness too. A nightmare! A real life horror tale! And I often think of Dracula as being a vivid allegory for the sexually transmitted blood disease that could even be spread to a child in the womb. It was therefore an eternal threat, never to die with the victim’s flesh – and perfectly personified in the character of the vampire.

But The Undead existed in literature well before Bram Stoker’s Dracula. James Malcolm Rymer created his demon in 1847, when writing Varney the Vampyre, a macabre literary best-seller with a great deal of sexy sucking and slurping which was serialized in Penny Dreadfuls; cheap newspapers sold upon the streets that the urban poor snatched up in droves ... and how they would have thrilled to read the start of Varney’s Feast of Blood - “How the graves give up their dead... how the night air hideous grows with shrieks!” –

The grave in question holds the corpse of an English aristocrat who, having been hung for some heinous deed, is then revived by a medical student, with echoes of Frankenstein perhaps? Sir Francis Varney then becomes the embodiment of the living dead, who is each night revived again when bathed in rays of moonlight, and immersed in darkest shadows he carries out depravities, feasting on young virgins' blood, until he eventually ends this spree – an end that I refer to in my novel, The Goddess and the Thief, where my narrator - a virgin herself - is suffering with a sore throat and wanders into her grandmother’s bedroom...and sees a bottle on the stand of Mrs Winslow’s Soothing syrup -

What harm could it do to sip at that ... such a tingling warmth in my throat and breast, and – well – how soothed I seemed to be when I lay on my grandmother’s quilt a while.... and soon became entirely lost in some musty yellowed papers. Had my grandmother read those ‘Feasts of Blood’? Such salacious tales they were! And Varney’s fate – how terrible – when, in the final installment, when consumed by guilt and dark despair, the vampire ended his own life in the flames of a volcano ... there to burn for the whole of eternity...

For all that excitement I fell asleep...but the vampire’s tale caused me to dream, and in that dream I saw a skull, a skull all burned and charred and black, which then began to speak to me. And its voice – it seemed familiar – when it asked, ‘Why dost thou shrink from death?’

That reference to a burned black skull is heavily linked to vampiric themes of a far more real nature - when I write of a religious sect, still in existence to this day: the Aghori, who worship Shiva, the god who dances and beats his drum to conjure realms of life – and death – to create all the good and the bad in the world'. And to purify their human souls, to achieve a oneness with their Lord, the Aghori see no horror in immersing themselves in the foulest decay, inhabiting Hindu burial grounds while consuming drugs and alcohol – even eating human excrement. It is also a custom - a trial of sorts - for every new member of that sect to find himself a human skull, from which he must drink human blood. And it is the drunken prophecy spoken by one such cannibal that we hear at the very opening of The Goddess and the Thief , when an English woman in India writes -

Benares, painting by Goodwin

There was a temple that looked like a palace. It gleamed like silver against black skies where a bright full moon was shining down upon the domes and balconies, and the ornate marble arches, and in every arch a deity, and every deity shimmering in the flare of torches set below. A pair of golden fretwork doors drew back to show a golden god... hailed by a thousand beating drums, the crashing of cymbals, the blaring of conches. I could not drag my eyes away, even though the god’s were closed. I kept thinking, ‘He cannot see me’. And yet, I knew he could, as if he could look into my soul through the gleaming ruby in his brow, or the ruby eyes of the cobra that coiled around his throat. That put me in mind of the devil in Hell, as did the trident in one of his hands. But then, the way he raised one palm – that seemed a benediction – and when a gust of air rose up, it was the strangest thing, because, I thought, “A gift, a blessing. A kiss from the lips of Shiva.”

Such sacrilegious thoughts I had...I forced myself to turn away, to run on down the steep stone steps that led me to the river’s shore...How wide it is, that river? I could barely see to the other side where the flames of fires were burning and such strange shadows dancing. It must be one of the funeral ‘ghats’, where the Hindoos go to cremate their dea... If only I’d not noticed that. The sudden stench of burning flesh ... and then, the hand upon my wrist... a hand with fingers more like claws, with nails filthy, cracked and long. And there the horror did not end. In the other hand he held a staff, a drum, and what looked like a human skull. He wore nothing more than a loincloth. His flesh was black and wrinkled. And the toothless face that leered above... I could only watch when he dropped my wrist, unable to speak when his fingers spread and lowered to rest on my belly. And just at that moment my baby kicked and that motion so sudden and violent that I gasped at the very shock of it. But it did bring me back to my senses again. I screamed. I pushed that wretch away. And he made no attempt to prevent me, only smiled as his hand was lifted, the palm extended forward, just like the golden god’s before. And then, he said the queerest thing: ‘Do not fear thine death. Death is the blessed sacrifice with which to glorify The Lord. The Lord will claim thy womb’s new fruit, the goddess thus to be reborn.’

Such sacrilegious thoughts I had...I forced myself to turn away, to run on down the steep stone steps that led me to the river’s shore...How wide it is, that river? I could barely see to the other side where the flames of fires were burning and such strange shadows dancing. It must be one of the funeral ‘ghats’, where the Hindoos go to cremate their dea... If only I’d not noticed that. The sudden stench of burning flesh ... and then, the hand upon my wrist... a hand with fingers more like claws, with nails filthy, cracked and long. And there the horror did not end. In the other hand he held a staff, a drum, and what looked like a human skull. He wore nothing more than a loincloth. His flesh was black and wrinkled. And the toothless face that leered above... I could only watch when he dropped my wrist, unable to speak when his fingers spread and lowered to rest on my belly. And just at that moment my baby kicked and that motion so sudden and violent that I gasped at the very shock of it. But it did bring me back to my senses again. I screamed. I pushed that wretch away. And he made no attempt to prevent me, only smiled as his hand was lifted, the palm extended forward, just like the golden god’s before. And then, he said the queerest thing: ‘Do not fear thine death. Death is the blessed sacrifice with which to glorify The Lord. The Lord will claim thy womb’s new fruit, the goddess thus to be reborn.’

Poor woman! To hear such a prophecy; a prophecy that will soon come true, to curse her, and the child in her womb – a child who then grows up to see gods, and ghosts – and human skulls – and thinking of skulls for one last time, I’ll end my talk with one more tale that may well have graced the pages of those Penny Dreadful magazines.

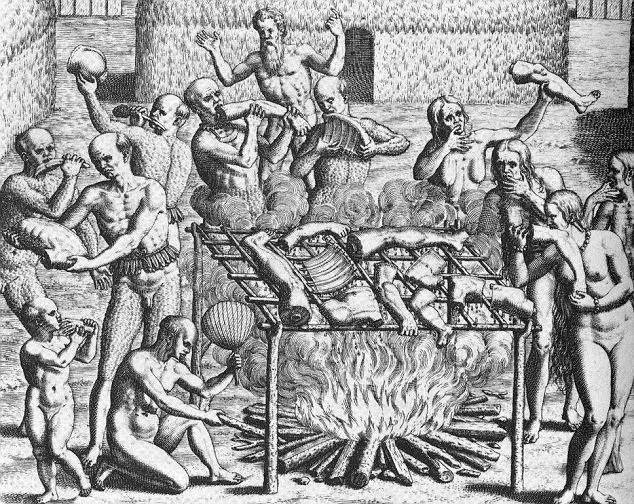

I wonder how many people today will have heard about ‘corpse medicine’. It was once practiced here in England, though it was in the 16th and 17th centuries when you would have been most likely to find certain types of medical men prescribing the eating of human remains as a cure for almost everything - never mind the way that body fat could be used in bandage poultices, or rubbed onto the feet for gout. The idea was crudely based upon what later became homeopathy - so blood for ailments of the blood – intestines for any belly complaints – and, as late as 1847 there is the report of an Englishman grinding up a human skull and mixing it with treacle, that culinary delight then spooned into his little daughter’s mouth - to stop her epileptic fits. Sadly, the cure was to fail! But where did he find the ingredients?

Well, Egyptian mummies were one source, not quite two-a-penny, but common enough for Victorian travellers to find if they really wanted to. And there were men nearer to home who were not at all averse to making a living from robbing graves. But I think that particular delight should be saved until another time...