I write gothic historical novels which are set in the Victorian era – and a great inspiration for that theme was a visit to Wilton's music hall - which resulted in my debut novel, The Somnambulist.

I still feel such a tingling thrill of excitement whenever I think of the evening when, with no idea whatsoever of what I would find on the other side, I passed through the flaking wooden doors and left the bustling East End behind to enter a world quite magical!

The grand chandelier and the mirrors once fixed in arched niches around the walls may now be long gone, but the metal barley twist pillars remain to support an ornate balcony. And it was during my visit, while seeing the light reflected on those that I felt myself almost transported in time, almost able to see the Victorian crowds, to hear the clatter and bang they made. The laughter. The shouting. The pop of champagne corks, all echoing around the walls from hall’s Victorian heyday.

But, of course, any beauty and elegance – and Wilton’s is very elegant despite its delapidated state – cannot hide the uglier truth that any mirrors of the past would also have reflected back. There would surely have been violent scenes such as fighting and thieving and drunkenness, not to mention those transactions made between gentlemen and prostitutes – although John Wilton, the hall’s proprietor, was always very keen to ensure that any whores who worked his hall were of a finer variety than those to be found in the Haymarket.

However that claim is questioned in my second novel, Elijah’s Mermaid– which exposes the hypocrisy that existed in the Victorian demi-monde – all the darkness and sin that lay beneath the so- called respectable surface of the realms of high art and literature. And all at a time when wealthy Toffs might visit the East End music halls to go ‘slumming’ with the labourers – quite happy to leave their wives at home to play their pianos in innocence as docile Angels of the Hearth.

In Elijah’s Mermaid, the excesses of the Demi-monde – all the Sin and Inebriation...the Lust and other such Wickedness - are witnessed at first hand by Elijah Lamb, a naïve young man from the countryside who has come to London to take up employment as a studio assistant for the artist, Osborne Black. But before going to live in Osborne’s house, Elijah visits Wilton’s hall – escorted there one evening by his somewhat older and louche Uncle Freddie; an occasion which Elijah will later recount in his diary –

Such a clamour of bodies. Such heat they gave off. And the smell of the place! Sweat and perfume and alcohol. The shouting. The laughing. The sparkle of mirrors set around, which reflected, not only the audience, but also the enormous chandelier beneath which, in the flaring of the limes, I was as dazzled as a hare when caught in the beam of the poacher’s lamps. But a glass or two of Freddie’s ‘phizz’ did somewhat alleviate my nerves, soon admiring the glints of light that caught on the balcony pillars around – though Freddie was pointing up to the stage where a monocled swell was walking on, beginning to sing some bawdy song.

Freddie was having the best of times, joining in with the chorus – calling to other acquaintances, or raising his glass to the women who blew kisses down from the balcony, one leaning so very far forward that her breasts dangled loose from her bodice when, ‘’Ello, Freddie,’ she screeched, ‘ain’t sin you in a while. Fancy a suck on me bubbies tonight?’

I had the impression that they had met before...in this world where my uncle seemed quite at ease – until someone new appeared at our table to whom he extended a chiller response, Freddie’s smile fallen into a sullen grimace through which he simply stated, ‘You!

The ‘You’ gentleman tipped his hat and replied in a lilting London drawl, ‘Indeed, it is I, Mr Hall. I spread my net very wide these days. Catch all manner of bits and bobs that way.’

He proceeded to make himself at home, pulling up a chair and sitting down, when he asked, ‘Has my friend’s personal preference changed? Is Cock Alley not to your taste these days?’ At that he gave me a lascivious wink, and while awaiting Freddie’s reply spent several tortuous moments arranging the folds of his overcoat, which was made of black velvet and very long. His whole personae was quite unique. He had straw-coloured hair held back in a ribbon, hanging half way down his narrow back. He had the most distinctive moustache, the hair on his face unusually fine, like silk ribbons those tusks drooped each side of his jaw. Added to that were his pursed rouged lips, and the frothings of lace at his collar and cuffs, and the flaring waistcoat beneath his coat, embroidered with mermaids, flowers and shells, all of which rendered his style to be that of some antique dandy conjured up from a bygone century. It transpired that he also had a taste for certain sorts of literature, suggesting that Frederick Hall might like to renew his professional interest in those ‘specialist publications which were always in demand with the punters’. At that he leaned forward, appearing more earnest, elbows propped on the table top, the palms of both hands pressed together hard, and the fingers steepled, as if in prayer. And that was when I noticed his nails, most being well over an inch in length, some tips being filed as sharp as knives, the others jagged where broken off. And above that most unnerving sight his clear blue eyes were narrowed to slits, which caused the thick layers of powder he wore to flake and split where wrinkles creased when, while awaiting Freddie’s response, he made a sly sideways glance at me, ‘You must tell me the name of your pretty young friend? Is he another protégé, a new writer employed by Hall & Co?’

Was I naïve or the victim of pride when so freely offering my name, my employment being an artist’s assistant, and also a photographer – to which boast he said I would be amazed at the sort of prices being paid for portraiture of ‘the intimate kind’. Next thing, he asked for whom I worked, and when I mentioned Osborne Black the queer fellow became all ears, his eyes positively gleaming when sitting back in his seat to pronounce, ‘What a serendipitous event!

As it turns out for Elijah Lamb that meeting at Wilton’s music hall leads on to a great deal more danger than any degree of good fortune.

But, one thing I have found in my writing career is how serendipity does play a part – such as when I was searching the internet for some early examples of photographs, with that art form playing a significant part in the story of Elijah’s Mermaid–

I found many tableaux of classic themes which provided me with a window into a certain Victorian world. This albumen print by William Lake Price, I used as a basis for some of Elijah’s own photographs – when he is just beginning to experiment with his camera and uses his author grandfather as a model for Quixote.

I also found the photographs of Julia Margaret Cameron, and really it was her distinctive style that I imagined Elijah creating of his grandfather and sister in their Herefordshire country home – and those images then being admired by the artist, Osborne Black.

For these glimpses of a time and place that would otherwise have been quite lost we have to thank men such as Henry Fox Talbot, a founding father of the English art – or science – of photography. And here, I’d like to quote something that Fox Talbot once wrote of photography, and these exact words are quoted in the pages of Elijah's Mermaid where they have a great significance as the mystery, art, and magic unfolds –

‘A person unacquainted with the process, if told that nothing of this was executed by hand, must imagine that one has at one’s call the Genius of Alladin’s Lamp. And, indeed, it may almost be said, that this is something of the same kind. It is a little bit of magic realised.’

Old Victorian photographs do possess something magical. (And if this is a subject that interests you, then I recommend a visit to Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire, which is where Henry Fox Talbot once lived and worked, and where there is now a museum dedicated to the science and art of photography). To see those old pictures of captured light, however faded or grainy they are, allow us the luxury of almost being time travellers - to really see the people then – what they wore – the glint of life in an eye – whereas, in previous ages, we can only look at portraits, and those were often idealised. So we think we know what Shakespeare looked like, but we know exactly how Dickens appeared, whether that be in his prime, or as the exhausted and over-worked man here depicted shortly before his death.

Such intimate portraiture – and the way it can illicit the most poignant emotional response – may also be why I’ve never been tempted to write about earlier historical times. Even so, I do realise that for many people, even the Victorian era already seems too ancient – too far away for us to reach.

Or is it? When researching on the internet, I came across this self portrait! My first thought was how similar this young man was to how I imagined Elijah Lamb. But then I was fascinated to find that this daguerratype – a photograph on glass named after its inventor, the Frenchman Louis Daguerre – was also the very first portrait of a human being, rather than a landscape or stationery object.

It was made in 1839 by Robert Cornelius who already had a great interest in the science of photography and the chemistry that was involved in improving the speed of exposure times. Here he is in Philadelphia, outside his family’s lamp-making shop, and despite this picture having been taken nearly two hundred years ago, Robert Cornelius looks to be as real as any other young man you might happen to pass on the street today. You could almost reach out and touch him, tap him on the shoulder, talk to him, get to know him. To me, he is very much ‘alive’.

In the fictional ‘reality’ of my novel, the artist hires Elijah Lamb to photograph the backgrounds that are used in his painted portraits – which is what many artists did at that time – using the new technology to aid them in their paintings, so that if the weather proved to be inclement, or when a view changed with the passing of time, the painter could have an aide memoir and continue to work in his studio.

One famous example of this is the Millais painting of Ophelia– an image that is also referred to in my novel. Most of us know the story of how the model, Lizzie Siddal, very nearly caught her death when she posed in a bath of cold water for hours. But, as well as the beautiful, pale ‘dead’ face, there is the most astonishing detail in the water and the plants in this picture – exactly the sort of detail that my artist, Osborne Black, is obsessive about in his own work.

This is because the Pre-Raphaelites liked to observe directly from nature, often working outside in the open air. In this case, Millias constructed a hut to one side of the Hogsmill River in Surry in which to sit when the weather was bad so that he could continue to work from life. But, when forced to return to the studio, it was through observing photographs that he could then continue to keep the precision in his art.

But returning to the subject of writing - and the subject of serendipity – whereas my chance visit to Wilton’s led to the writing of The Somnambulist, the main inspiration for Elijah’s Mermaid dates back to the time of my childhood – when – at around seven years old, I went to the local library and took home an edition of Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby.

I found that story magical, with all of the promising allure of any ‘Once upon a time...’ or the ‘far far away of another land...’ But, as in the best children’s literature, this Victorian story goes deeper than I could have realised back then. It contains a message for adults too – especially those Victorians who read when it was first published in 1862, when they would have been perfectly aware that Charles Kingsley was making a social and political stand regarding the dreadful conditions in which many children were forced to work. Indeed, when reading again as an adult, as well as the basic storyline, I found pages of ranting sermons, and lists of all the ills in the worlds – some of which would be very offensive today regarding other races and creeds.

My childhood version was surely abridged. I don’t remember those lists at all. But I do remember the pictures - the enchanting illustrations by the artist, Jessie Willcox Smith. And, for those who do not know the tale, Kingsley’s book is all about little Tom, an orphan who works as a chimney sweep, who, when trying to wash himself clean in a stream, happens to fall asleep and drown – only then to wake and find himself reborn as a water baby. In this new underwater existence, Tom has a great many adventures. But, for me, it is the earlier chapters that have always lingered in my mind – the ones that convey the darkness of the world in which the orphan lived – all the crime and filth and poverty – and how that contrasted with the life of a rich little girl called Ellie, who looked just like an angel and who lived in the purest, whitest world.

In Elijah’s Mermaid, those two worlds are reimagined when I have one orphaned child called Pearl being raised in a London brothel, while two others (Elijah and Lily, who also happen to be twins) grow up in an innocent countryside idyll with their grandfather, an author of fairy tales. Those two worlds are kept entirely apart until all three reach puberty and visit a London freak show tent, into which they have been lured on the hope of seeing a 'real mermaid'. Whatever they chance to view – and it is rather dramatic – it is at that point their paths converge, just as others so many often did in nineteenth-century society, where nothing was ever as black and white as the moralists would have liked to think.

Decadence was common, if you only knew where to look for it. Just as men sought out whores in the music halls, they might also find them on the streets, in the theatres or pleasure gardens...and often with girls who were underage. When the age of consent was only twelve this conjures the most fearful scenes.

It is almost unbearable to think that in the Victorian age it was not an uncommon thing for parents to play the parts of pimps, not necessarily with evil intent, but because they had no option but to find the money with which to provide the food and clothes for their families: to pay for a roof above their heads – or else to starve and be destitute. When it came to such stark realities – a choice between matters of life and death – even though it may disgust us now, prostitution was often viewed as being the lesser evil.

But more evils lurked in sin and sex. And wherever prostitutes were found, and whatever age they might happen to be, a very real consequence of any such encounter was that of contracting venereal disease.

This is the wax model of the face of a man who has died of syphilis – that infection being rampant in nineteenth-century England. Today, we have antibiotics which can cure such infections easily. Then, there was no hope at all. For the Victorians – a culture who were already obsessed with death – it was true to say that sex could kill. Such was the hysteria that at one point a law was passed so that any woman on the streets could be arrested and physically examined for showing signs of the disease. Not men, you note – just women! And, as you can imagine the system could often be abused, with complaints from many an innocent soul who was apprehended when walking alone.

Those who were infected could be placed in isolation, in medical institutions such as the London Lock Hospital – a cross between a prison and a convalescent clinic where it was hoped that sinful souls were saved and prepared for heaven. While those patients suffered hellishly, kept away from the public eye, well out of sight and out of mind, the highly infectious but physically well continued to spread the vile disease.

Many an innocent bride would be infected on her wedding night, after which the disease could lie dormant for years, hiding in the blood’s circulatory system and finding its way to a child in the womb. In the later stages it could produce some terrible lingering symptoms – when apart from the weakening of the heart, lesions would affect the bones, the skin and the nervous tissues. Any ‘cures’ on offer then were almost as bad as the illness itself, which led to the popular saying,‘One night of love with Venus...a lifetime spent with Mercury.’

Mercury – what we now understand to be a toxic metal – was taken in the form of pills, or smeared on the flesh as ointment, or else inhaled in a steam bath. It might alleviate some of the symptoms but was most certainly not a cure. It had some horrible side affects, resulting in the loss of teeth, or ulcers or further damage to nerves. And it very often led to death. Yet, with no other option, those who had the means to pay could use it to try and delay their fates. But ultimately, all were doomed. Syphilis was the great leveller. It did not discriminate between rich, or poor – or famous.

This is a photograph of Bram Stoker. The author of Dracula was a long time sufferer of the disease – even though he was said to have met his end from physical exhaustion – that popular Victorian euphemism when referring to venereal disease. But I always think, when you know that fact, you might consider differently the nature of Bram Stoker’s book – seeing anew in its pages a description of a corruption of the blood: a corruption which can be passed on even when those affected are ‘dead’ – a horrible and immortal scourge.

And here is Mrs Beeton who, before I knew any better, I always imagined as someone officious, portly, and middle-aged – something of a dragon of the range rather than a Domestic Goddess. In fact, she died before she was thirty, and from complications of childbirth when her health was much weakened by syphilis. She had been infected by Samuel, her husband. No doubt he was unwittingly trapped when during his bachelor years he would have sought fulfillment in the only way he could – the only way offered to many young men of a certain social class back then, which was via the services of prostitutes.

But, what misery that led to! During her short adult life Isabella Beeton had the misfortune to suffer several miscarriages – another blight of the disease. Two living sons went on to die from congenital complications. One who was aged only three months, another lived to be three years.

In Elijah’s Mermaid, Mrs Hibbert is the madam of the brothel in which the child, Pearl, is raised – who was found when only a baby, when floating in the river Thames. Mrs Hibbert conceals her face in veils and apart from the obvious, those veils symbolise the depravities of the Victorian demi-monde - all the evils concealed in darkness, that contrast between the day and the night - between the pure and the corrupt.

This is another painting by Millais. It is called A Somnambulist and for those of you who have read my first novel, you will know of its significance. But in Elijah’s Mermaid there is another character who also takes to walking out upon the night-time London streets.

Sleepwalking was a popular theme in Victorian Sensation literature, indicting ignorance or deception, or the mysteries of the occult. Some say that the Millais painting was based on La Sonnambula, a Bellini operetta – the success of which could be compared to Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musicals now. But personally, I prefer to think that it was The Woman in White, the novel by Wilkie Collins, that provided the true inspiration for such a darkly brooding scene, where – being at odds with all rigid Victorian sensibilities – a young woman is in peril, walking alone in the dead of night, her virtue and reputation at risk, never mind the risk that she will fall to her death on the rocks below.

But then, as as many Pre-Raphaelite paintings are full of symbols and ‘stories within stories’, I think we might very well assume that those are the rocks of moral doom! And speaking of rocks of moral doom – this painting which is called A Mermaid, by the artist John William Waterhouse – is one that greatly inspired me when writing Elijah’s Mermaid: in particular for the character of Pearl, the girl who spends her childhood in a house where the walls have murals of mermaids. There, she is pampered and cossetted and kept in relative innocence until, at the age of fourteen, she is sold to the highest bidder. In this case that man is Osborne Black, the artist who has an obsession with water, and who, from that point onwards, constantly wishes to paint his muse in the form of a nymph or mermaid.

Both paintings are dramatic. Both encapsulate so much about Victorian literature, which was anything but stuffy or dry, often relishing in scandalous themes, such as illicit affairs, bigamous marriages, or divorce – the stigma of which, in reality, could lead to ruin and social disgrace. There were orphans or illegitimate children. There were stolen or lost inheritances. There were women gone mad and confined to asylums, and murders and other audacious crimes – not to mention the vengeful ghosts upon which the truly ‘sensational’ plots might twist and turn so dramatically that the reader was left not only thrilled but often left panting in anticipation and desperate for more to come.

The reason for that was because most of these ‘page turners’ were serialised in weekly or monthly magazines before being published up as books. It was therefore in the writers’ interests to keep every one of their readers ‘crying, laughing, waiting’ – hanging – metaphorically speaking, upon the edge of that very cliff along which the Millais Somnambulist walked. And, for probably the very first time in the history of the printed word, members of every social class – from the grandest ladies in their parlours, to the kitchen staff in the basements below, would be reading the same thrilling stories. Stories such as Collins’The Woman in White, or Dickens’ David Copperfield– all with characters larger than life, who would become as ‘intimately known’ to their Victorian readership as the most popular actors in our televised soap operas today.

It is due to their enduring appeal that many Victorian classics are still being adapted for our screens. There is something about the simmering tension, the menace of murky, candle-lit worlds that I always find alluring. Even as a little girl I loved to watch all the old black and white films that were shown on Sunday afternoons, when I’d snuggle up on the sofa with my mother and aunts, and lose myself in dramatic tales such as that of Madame Bovary, or Wuthering Heights, or The Barretts of Wimpole Street, or Jane Eyre, or Great Expectations (which I saw again very recently, and found just as wonderful as I’d remembered). And above you can see the haunting face of Ingrid Bergman in Fanny by Gaslight.

I suppose it was no surprise when I set my own stories in such a world, and with many real settings that are still existence now to provide me with inspiration.

In Elijah’s Mermaid, just as in The Somnambulist before, I have taken a Herefordshire setting – in this case the village of Kingsland where I spent a great deal of my youth, where a house that was once the rectory has a stream at the end of its garden. It is here that my foundling children, Lily and Elijah Lamb, one day take a jam jar in the hope of catching a water baby. And when that particular venture fails they make a grotto from stones and shells, hoping instead to create a place that might lure a mermaid to come and live.

Meanwhile, the novel’s real ‘mermaid’, Pearl, is shivering and frightened while having her portrait painted in a subterranean cavern, where the walls are covered with millions of shells. This setting is based on the Margate Shell Grotto which, if you have not been there, I highly recommend. It is the most astonishing place, and one of the greatest mystery as no-one knows to this very day when, or why, the grotto was made.

Chiswick House is another glorious setting, and one which I know very well from those years I spent living in that part of London. In my novel, it is in these beautiful gardens that Pearl is sketched as a water nymph while she lies beside the temple pool. But what I didn’t know until mid way through writing this scene was that, while researching asylums for another aspect of my plot, I discovered that in the Victorian era Chiswick House had also been leased out as such an institution.

The house is no longer used as such but has been restored to its original glory, which dates back to 1729 when the third Earl of Burlington spared no expense in the building of the villa and garden which were used to display his art treasures, and also for entertaining friends. Each successive family member then made their own mark on the estate. (At one point the gardens housed a menagerie of exotic animals.) It was also leased to the Prince of Wales, until, in 1893 that tenure fell to the Tuke Brothers who created their asylum, where among other wealthy patients there resided Millais’ sister in law. The troubled Sophy is the girl who features in some of Millais' works, and to whom I hope the Doctor Tukes were kinder than those wicked souls who appear in Elijah’s Mermaid– in which I explore another sort of Victorian demi-monde: that being the way in which the sane could be hidden away behind locked doors, and on little more than the whim of a husband or other male relative, who could pay two doctors to sign the forms which then left the deceiver free to pursue affairs of the heart elsewhere, or perhaps to steal an inheritance.

There is another location featuring in Elijah’s Mermaid which has now been forever lost to us – and that is the Cremorne Pleasure Gardens which existed in Chelsea, on The Thames, which is very near to Cheyne Walk where my brothel, The House of the Mermaids, is set. This picture by Phoebus Levin shows the gardens as I imagined them on the day when Lily and Elijah Lamb visit there and meet with Pearl, when all three hope to see a mermaid, and find themselves confronted instead by something truly hideous.

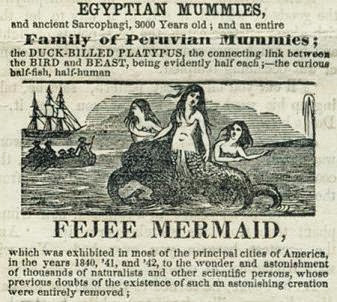

This is a Fee-jee mermaid. Many such monstrosities were produced in Victorian times, to be displayed in travelling shows. A taxidermist’s hybrid (usually half-monkey and half-fish), the body parts were preserved and stuffed, and then joined together to make one whole.

It’s hard to imagine anyone being convinced that these horrors could be real. But, I think we need to remember this was a time when people were generally more naïve. And this was also when Darwin’s work about evolution was coming to light – so perhaps it was not such a stretch of the imagination to think that it might be possible for such a creature to have evolved.

I know, when I was a little girl, I would have liked for nothing more than to find that mermaids and water babies really could exist. Of course, I was not the only one. There is a lovely story relating to the Kingsley’s novel, when the five year old grandson of the scientist Thomas Huxley saw an illustration of a water baby caught in a bottle and then wrote this charming letter –

Dear Grandpater – Have you seen a Waterbaby? Did you put it in a bottle? Did it wonder if it could get out? Could I see it some day? – Your loving Julian

To which his grandpater wrote this reply:

My dear Julian –

I could never make sure about that Water Baby. I have seen Babies in water and Babies in bottles; the Baby in the water was not in a bottle and the Baby in the bottle was not in water. My friend who wrote the story of the Water Baby was a very kind man and very clever. Perhaps he thought I could see as much in the water as he did – There are some people who see a great deal and some who see very little in the same things. When you grow up I dare say you will be one of the great-deal seers, and see things more wonderful than the Water Babies where other folks can see nothing.

For Lily and Elijah Lamb, seeing the Fee-jee mermaid is of enormous importance, not because it makes them believe in such things, but because it is the turning point when their hopes are crushed and they grow up, to leave such childish dreams behind. As for Pearl, something of a freak herself, having been born with webbed toes on her feet, she thinks of the mother she never knew, who drowned around the time of her birth, and who tried to kill her child as well when she jumped to the Thames from old Battersea Bridge.

And that is when my novel begins – and also where this article ends, with an extract taken from the book, just after a newspaper cutting – an article from The Times newspaper which is dated May 1850, and headed MYSTERIOUS DEATH. It tells of a woman found in the Thames, who is wearing a long black cloak, adorned with black ostrich feathers, and who has no injuries to her person, except for the signs of a recent childbirth and the suffocation of her lungs, which leads the coroner to pass what was then the all too common verdict of: ‘Found Drowned’ – as depicted in the painting above by the artist George Frederick Watts.

After that newspaper cutting we begin to read the narrative of Pearl, and have our first brief introductions to the Madam and the Pimp who share her home in Cheyne Walk -

That May night of my ‘birth’, of my finding, many marvels and wonders were seen, and every one of them noted down in Mrs Hibbert’s Book of Events. Thus –

There was a cabman who worked Cremorne Gardens who, come to the end of his shift for the night, was about to head home across Battersea Bridge when he saw an angel flying by. In the moonlight her ebony wings glistened silver, snapping and billowing out through the air, and two black feathers floated down to brush, like a kiss, against his cheek.

A warehouse nightwatchman at St Katharine Docks swore blind to have heard a mermaid’s song, and such a sweet melody it was, ringing clear as a bell through the dense fogged air. A waterman down Wandsworth way claimed to have seen a nymph that dawn. He told how her hair shimmered over black waters, a rippling fan of gold.

And then, there was the comet, described by so many that night; its tail a streaking fire of light as it followed the sinuous bend of the Thames, until its arcing trajectory plunged far out in the sea beyond Margate, at which point there was nothing left to see but a rising plume of fizzing steam.

I doubt that any such tales were true; more likely to have been conjured up by Mrs Hibbert’s warped genius – Mrs Hibbert, pronounced Mrs ‘eebair’, who held court in the House of the Mermaids, a most prestigious Chelsea abode which overlooked the River Thames, from where she concocted fantastical bait with which to lure the clientele through the doors of her maison de tolerance. And with every one of them being toffs – aristocrats, barristers, men of the cloth – to retain their investment in her house she indulged those gentlemen’s every whim. She offered a glittering palace of dreams where they could dab the finest whores who played the part of dutiful wives, but without any matrimonial bonds.

Privately, she called them dupes. The things they will believe, ma che`re! But then she was very persuasive and I was never more beguiled than when hearing my very own story told, with Mrs Hibbert’s dulcet tones as soothing as any lullaby – You were sent to us from the mermaids...you are the Wondrous Water Child, the Living Jewel from the Oyster Beds, Spawned from the Loins of Old Father Thames and the Fishy Womb of his Mermaid Bride.

But the truth always was more prosaic than that. The truth is that I was the bastard child saved from the river that night when my mother drowned herself for shame. And the only name I have ever known is the one Mrs Hibbert chose to bestow. And the very first memory I have is the sound of her lulling, lilting voice as she called for me to enter a room with lovely pictures all over the walls, walls painted with silvers, blues and greens, with fishes, and mermaids with golden hair – hair wreathed with ribbons, with stars, with pearls.

My hair was once yellow and curling. I wore a crown of shells. Beneath lace skirts my legs were bare, no stockings or shoes to hide my feet, the stubby wedges where toes should be, tingling and cold on the marble tiles. I wanted to run back upstairs to my room but I knew Tip Thomas was standing close, his lips twisted into a snide grimace between whiskers as pale as walrus tusks, and the daggers of his fingernails digging down through the flesh of my shoulders, and me more frightened of riling him than whatever was waiting in that room, from where Mrs Hibbert coaxed again – ‘Come, ma che`re . . . ma petite nymphe.’

Mrs Hibbert held out her black-‐gloved hands and crooned through the mesh of her thick black veils, ‘Come play with my friends, my pretty Pearl.’

.jpg)