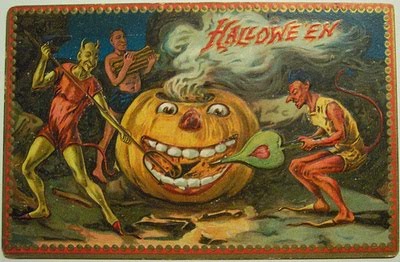

For many of us today, Halloween is a commercial tradition made popular in America, where pumpkin-head lanterns in front of doors lure children to come and Trick-or-Treat while dressed as skeletons, witches, or ghosts – and sometimes even Dracula.

But the supernatural or ‘Undead’ do have historical relevance to the origins of Halloween. Once known as Samain or ‘Sow in’, this ancient Celtic festival signified the beginning of the New Year when the harvest had been gathered in and the dread dark winter lay ahead. On its eve, October 31st, the divisions between the living and dead were said to draw back like a curtain, allowing supernatural folk and the souls of the dead to re-enter the world. Bonfires and fancy dress parades might drive the risen dead away. If not, they were placated with food, left in bowls outside locked doors.

The advent of Christianity then appropriated those customs, with ‘All- Hallowmas’ or ‘All Saint’s Day’ revering saints and martyrs instead of ghouls. And yet, as so often when cultures merge, remnants of both traditions remained. The gifts of food became ‘soul cakes’ left out for the homeless and hungry, in return for which they prayed for the dead. (Would our Trick-or-Treaters agree to that?)

Many other old superstitions persisted. American Irish émigrés replaced the carving of turnip heads with pumpkin Jack-o-Lanterns – Jack being the folklore rogue who offended both the Devil and God, thereafter excluded from Heaven and Hell and walking the earth till Judgment Day.

Other Celtic customs were described in Rabbie Burns’ poem, Halloween – in which fairies dance on a moonlit night while youths go out to the countryside, singing songs, telling spooky tales and jokes, or partaking in fortune-telling games; such as eating apples while looking in mirrors and that way creating a magic spell to reveal the face of a future love.

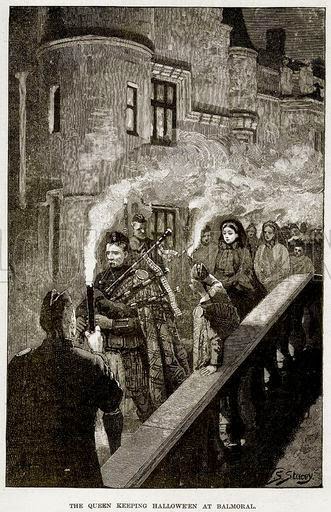

Whether Queen Victoria ever peered into such a mirror, she certainly entered the spirit of things when joining the annual fire-lit procession that took place at Balmoral castle. However, back in England, the rise of the Protestant Church meant that Halloween rituals had fallen away – perhaps explaining Charles Dickens’ shock when he travelled to America and witnessed the general festivities there. But what really piqued his interest, rather than the parties and popular games (such a Pin the Tail on the Donkey, or Blind Man’s Buff, or Bobbing for Apples – when the winner would be the next to wed) was the morbid fascination with ghosts.

It is surely no coincidence that after returning to England he wrote A Christmas Carol, in which spirits and future predictions abound. Other established authors went on to peel back age-old layers of myth to reimagine ‘All Hallows’ Eve’ – the genre soon very popular in poetry, art and literature; with tales of children stolen by fairies, or mirrors exposing some ghastly event, or women who wailed by misty graves – and all rendered yet more sinister when read by flickering candlelight to provide an eerie atmosphere.

The Victorians reveled in frightening tales. More than that, they embraced the culture of death, many visiting spiritualist mediums, or commissioning spirit photographers; the living duped into the belief that crudely exposed double negatives had captured some vision of their dead: all those veiled apparitions that lingered in shadows, and no longer just at Halloween. The image above is somewhat tongue in cheek, although others were taken more seriously - and the night of October 31st still holds a particular allure. Whether linked to innocent children’s games, or the horror films we view on screens there is nothing quite like a Halloween thrill.

The text of this article was first published in The Independent newspaper.