“The past is foreign country: they do things differently there.”

L.P Hartley’s The Go Between.

Any writer of historical fiction almost needs to become a time-traveller, to ‘go native’ and familiarise themselves with the cultural workings of the 'foreign place' in which their story will be set – to draw their reader into that world without qualms as to authenticity regarding the characters, settings, or themes that, if placed in a modern novel, might seem entirely alien. A good starting point is to read the work of established authors, those from the nineteenth century, and the best of the Neo-Victorians now. That way an author’s ear can attune to the nuances, rhythm and tone of the language that was used 'back then'.

Charles Dickens

My personal Victorian favourites are Wilkie Collins, the Brontes, and Thomas Hardy; each one of these writers offering a unique and distinctive style to define the age they represent. But, of all the Victorian writers, Dickens is considered by most to be the master of the era, with his storylines rising above mere plot and offering social commentary on almost every aspect of the world which he inhabited. However, a word of warning here. Attempts to emulate his work today can result in clichéd parody in any but the most skilful hands. A writer should be brave enough to develop their own personal voice and tone, albeit while following the ‘rules’ or restrictions of the genre.

Not all nineteenth century literature adhered to Dickens’ formal tone. Moby Dick, written in 1851, begins with these strikingly ‘modern’ lines – “Call me Ishmael. Some years ago – never mind how long precisely – having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen, and regulating the circulation…especially when my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off…”

There is still the formal Victorian phrasing to anchor us in the era, as exhibited in the phrase: ‘requires a high moral principle’. But at the same time Melville creates a very strong vernacular; entirely original. A real, living character whose voice could belong to any age, and who draws us directly into his world.

It has to be admitted that Melville was American. Many writers prefer to emulate the more English tradition of ‘Victoriana’ – that which has been so well-observed by the modern-day author Charles Palliser. According to many reviews, his novel The Quincunx ‘out Dickensed’ Dickens himself. Indeed, almost all ‘Sensation’ themes are covered in this lengthy book, with lost or stolen inheritances, laudanum-addicted governesses, dens of thieves, and asylums, along with doomed affairs of the heart. What’s more the story’s narrator is called John Huffam – the middle names of Charles Dickens himself. An audacious decision, but justified, because Palliser’s writing is superb.

![]()

Sarah Waters, who also excels in the genre, uses a sparer lyrical prose. She is rarely florid or overblown, as illustrated in these lines taken from the start of Fingersmith – where the reader is immediately toldthat the narrator has been orphaned; a common Victorian theme, around which secrets and mysteries can be woven into complex plots – “My name, in those days, was Susan Trinder. People called me Sue. I know the year I was born in, but for many years I did not know the date, and took my birthday at Christmas. I believe I am an orphan. My mother I know is dead. But I never saw her, she was nothing to me.”

![]()

Similarly, such clues are laid inThe Meaning of Night by Michael Cox, another stunning ‘Victorian’ novel which begins –“After killing the red-haired man, I took myself off to Quinn’s for an oyster supper.It had been surprisingly – almost laughably – easy. I had followed him for some distance, after first observing him in Threadneedle-street. I cannot say why I decided it should be him, and not one of the others on whom my searching eye had alighted that evening.”

The novel is ‘placed’ immediately by the archaic use of ‘Threadneedle-street’– and the fact of the oyster supper; a common meal in Victorian times and not the luxury food of today. The language also has a formality with words such as ‘had alighted’, which leaves the reader in no doubt that the genre is Victorian.

Another important factor for the writer of historical fiction is to ensure accurate scene descriptions. Inspiration is not that hard to find, with many of us still surrounded by Victorian architecture now. All the houses, shops, the theatres and bars from which our settings can be derived. The transport must be imagined, of course – the sounds of creaking carriages – the jangling of the reins – the clopping of the horse’s hooves – the rhythmic chugging of the trains, exuding clouds of cinder-flecked steam. And, as depicted in one of my novels, the common fears that “the motion and velocity might cause such a pressure inside our brains as to risk a fatal injury – a nose bleed at the very least.”

![]()

The expansion of the railways led to another common theme in Victorian novels. Train travel enabled the movement of a mass population – mainly coming from the countryside while searching for work in the city. These two settings often lead to a blunt comparison between innocence and depravity. Still, many continued to travel to London to seek their fates and fortunes – whether for better or for worse.

![]()

The city has, to this very day, a wealth of Victorian settings. A wonderful resource for any writer is to be found in Kensington, where No 18 Stafford Terrace (which belonged to Edward Linley Sambourne, a famed cartoonist for the satirical magazine Punch) remains just as it would have been in its Victorian heyday. There are Chinese ceramics and Turkey rugs, Morris wallpapers and stained-glass windows – not to mention the letters, the diaries and bills that provide an accurate insight into the running of such a house. For those unable to visit, there are the objects in museums, the documents found in libraries, or via a search on the Internet where many paintings and photographs are stored.

The nineteenth century saw the dawn of the science of photography and what a treasure that has left us. Victorian scholars have a distinct advantage over those of earlier centuries, for what better way to get a true sense of interior or exterior scenes, to study the fashions that were worn, or to catch the glint of life in an eye. I can only agree with Henry Fox Talbot, one of the pioneers of the art, who described the photographic art as ‘the genius of Alladin’s Lamp…a little bit of magic realised.’

As to the day to day running of any Victorian residence, the relentless slog of housework would have lacked any magic at all. But do not take my word for it. Why not read Judith Flanders’ The Victorian House, or go to an original source in Mrs Beeton’s Household Management.

In fact, Mrs Beeton offers advice on almost any subject, from cooking, to fashion, or medicine. Her words also occur in my novel, The Somnambulist, when my narrator quotes the book as a means of objecting to the clothes that her mother wants her to wear – “I was looking through Mrs Beeton’s book, and she wrote several chapter on fashion, and with regard to a young woman’s dress her advice is very specific indeed. She says that” – and I had this memorized for such a moment of revolt – “its colour harmonise with her complexion, and its size and pattern with her figure, that its tint allow of its being worn with the other garments she possesses.”

Many other contemporary factual works are still available today. Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor is surprisingly readable while giving a detailed insight into grim social realities. These studies were very useful to me when researching the Victorian demi-monde, as was My Secret Life by Walter.

Walter was a shocking libertine whose pursuit of physical gratification led to many a melodramatic encounter – and the exploration of a world that could not be more different to that which is generally perceived as the moral, upstanding society over which Queen Victoria ruled with her iron rod of respectability.

Walter, the far less ruly child, would surely have visited Wilton’s (a music hall setting used in my novels) with all of its night-time clatter and bang, where the prostitutes called from the balcony to those who sat at tables below - where the glisten of the lime lights would glance off the gleaming metal of the barley twists posts around the hall.

No doubt Walter would also have loved Cremorne – the Chelsea pleasure gardens described in my novel, Elijah’s Mermaid. The grounds were eventually closed down due to lewd behaviour, and sadly nothing now remains but a pair of ornate iron gates.

Cremorne Gardens by Phoebus Levin 1864

Unable to visit the actual place I still immersed myself in its atmosphere by reading contemporary articles printed in Victorian newspapers (the archives are still available online). I looked at paintings and adverts to gradually built a vivid scene inside my mind of the lush lawns with their statues and fountains, and the banqueting hall, and a hot air balloon, and lavish theatrical displays – such as that performed by the Beckwith Frog who swam in a great glass aquarium along with several living fish.

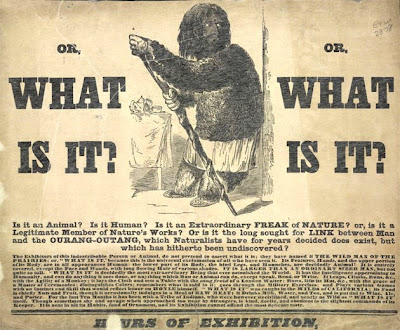

Freak shows were also popular as an entertainment form, though the mermaid display in my novel is purely the product of imagination. Even so, that image was inspired when reading about the Feejee Mermaids; the hideous monstrosities created by grafting a monkey’s remains onto the body of a fish. Imagine the smell smell of that!

![]()

Which brings me to another writing prop to further enhance a Victorian world, albeit one invisible – that being the sense of smell.It may well be a cliché when describing nineteenth century scenes to allude to the stench of filthy streets, but it would be wrong to ignore the fact of the constant odour of rotting food, the rising up of fetid drains, or the effluence from horses – all of which elicits a strong response from a character in Elijah’s Mermaid, who has come on a visit to London and is almost overcome by – “…sweat from the horses, and piss from the horses, though I should be used to such farmyard smells with plenty of muck in the countryside. But, in London, that perfume was too intense, as if every passenger in our cab had managed to step in a turd on the pavement, and that mess still stuck to the soles of our feet, firmly refusing to fade away.”

A writer might also think ‘outside the box’, revealing less obvious fragrances, which – in the case of The Somnambulist– was the smell of a popular perfume that came to have great significance within the novel’s plot. For this, I employed the Internet, seeking out aromas that a Victorian gentleman might use. I discovered Penhaligon’s Hammam Bouquet, first produced in 1872 and described by the manufacturers as: ‘animalic and golden…warm and mature, redolent of old books, powdered resins and ancient rooms. At its heart is the dusky Turkish rose, with jasmine, woods, musk and powdery orris.’ Quite a vivid description I’m sure you’ll agree. And, quite a serendipity – because, after the book’spublication, I realised that Hammam’s Bouquet is still being produced to this very day. I couldn’t wait to buy some, to lift out the bottle’s stopper and breathe in the vivid scent that I had only imagined before: to close my eyes and step right back into a lost Victorian world.

.jpg)