I was born and spent my childhood in the English county of Herefordshire, so it's really little wonder that it features so strongly in my books.

Having gone to school in Leominster, a medieval market town, I then travelled north to Sheffield where I went to university ~ studying English Literature; with my favourite module on that course being the Victorian novel.

Three years later I went back home again and spent three months at Hereford Technical College on a graduate secretarial course – after which I went to London for a job on the Telegraph Sunday Magazine, with the formal title of my post being Editorial Assistant - though I actually did all sorts things; including on one occasion dressing up as a Victorian maid for one of the magazine’s Christmas editions.

Modelling was not for me, and I soon moved on to another job; this time at George Allen & Unwin, a small independent publishing house situated in Museum Street, just opposite the British Museum. Sadly, that business is gone now. No-one sits in the attic as I once did, next to sputtering gas fire, surrounded by a giant wall of printed paper manuscripts.

But the offices in Ruskin house ... well, that lovely old building is still there. And I still like to wander past it if I’m ever in the area.

Allen & Unwin’s most famous author was J R R Tolkien, and something I loved about that job was seeing all the artwork that came in for his illustrated books. I think that’s what made me realise that, as well as enjoying stories I’d always loved painting and drawing too – ever since I was little girl when a lovely teacher called Mrs Cook was kind enough to encourage me; though since going to university I’d hardly thought of art at all.

However, when I had a baby and suffered complications I started to work from home instead, setting up a business designing mainly greetings cards. And, as is the way of things, before I even knew it 20 years of my life had gone flying by. My daughter had grown up herself and left home for university ... and one day I found myself wondering, well, is this the job I want to do for the rest of my natural working life. And, if not, what would I do instead?

I already knew the answer. It had always been simmering under the surface. Because ever since I’d been a child I’d always had stories inside my head, and now I was making pictures with words instead of pens and paints.

I’ve written three Victorian novels, all published by Orion Books. They are: The Somnambulist, Elijah’s Mermaid, and The Goddess and The Thief . Each of the stories stands alone, with different characters and plots. But, they are all mysterious and somewhat gothic in their tone, and two of them ~ the first two ~ were also heavily inspired by own life in Herefordshire.

![]()

My first novel, The Somnambulist takes its title from a painting by the Pre-Raphaelite artist, Millais, which is called A Somnambulist. You’ll see the size and scale of it in this photograph that my agent took at Bonhams Auction House in London, just the day before the novel's release when, quite by coincidence, the painting was being sold on behalf of Bolton Council. Up until that point in time it been kept it in storage, so it really was a thrill for me to see it in reality ~ and to realise how big it was because, having only seen it through the glass of my computer screen, I imaged it was much smaller - - as described here by Phoebe Turner, the narrator of The Somnambulist ...

![]()

“Halfway up the stairs on the little half landing, the copy of a Millais was hung ... and it showed a young woman with flowing dark hair, wearing no more than a thin cotton gown as she walked at the perilous edge of a cliff. She carried a candle, but no flame had been lit, and I always feared she might slip to her death, dashed on the rocks in a cold grey sea.

Some thought it was based on a popular novel, the one called The Woman in White. Others said that an opera inspired it, and that woman the very spit of Aunt Cissy when she was singing the part of Amina, in Bellini’s La Sonnambula.”

Well, whether it had been inspired by a novel or an opera, both were based around a ‘somnambulist’ ~ which simply means a sleepwalker ~ an image that was very strong in Victorian art and literature:. It represented repressed sexuality, or of being blinded to the truth through ignorance, or deception. It could also indicate a soul being under the influence of the occult; all of which are there to see in this dark, and eerie night-time scene ~ and all of which you’ll also find within my novel’s storyline, where a vulnerable young woman is walking alone in the dead of night, dressed in only her nightgown, with her virtue and reputation at risk, never mind ~ as my narrator fears ~ falling to her death on the rocks below. Because, as so many Pre-Raphaelite paintings were full of symbols and ‘stories within stories’, I think it’s safe enough to say that these are the rocks of moral doom.

Unlike many other Pre-Raphaelite paintings, this isn’t pretty or very romantic, and perhaps that’s why it didn’t fetch a huge price at Bonham’s auction house. It sold for around £60,000 pounds. But it really does encapsulate Victorian Sensation literature, which was often less stuffy or prudish than we might imagine now; relishing in salacious themes, such as illicit love affairs or the scandal of divorce ~ the stigma of which could often lead to complete and utter social disgrace. The writers, and readers, of these books relished in sordid goings on, with the pages regularly filled with misdirected and damning letters, with orphaned or illegitimate children, with stolen or lost inheritances, or women gone mad and confined to asylums. There would also be drugs or poisons. There’d be murders and other audacious crimes, not to mention the séances and ghosts upon which the plots might twist and turn to leave the reader ~ not only thrilled ~ but often left panting for more, and more. And because most of these ‘page turners’ were serialised in weekly magazines before they were ever published as books, it was in the writers’ interests to leave their readers hanging at the end of every chapter ~ metaphorically speaking as if they were teetering on the edge of the cliff where our Somnambulist walks.

These novels were read in huge quantities too. Due to industrialization, and the lower costs of printing, for the very first time in history members of every social class ~ from the grandest ladies in their parlours, to the kitchen staff in the basements below ~ could read the same exciting tales, where the ‘gothic’, or larger than life characters would become as ‘intimately known’ as the actors in TV soaps today; or those who act in our favourite films.

When I was a little girl I loved the old black-and-white feature films, shown on TV on Sunday afternoons. I’d snuggle up with my mother or aunts, and lose myself in old fashioned worlds. Worlds such as Madame Bovary, or Jane Eyre, or Great Expectations. Or there might be The Barratts of Wimple Street, or Wuthering Heights, or Fanny by Gaslight ... well, I’m sure you’ll have your favourites too.

For myself, I couldn’t get enough of all those murky, candle-lit rooms, or the shimmering fizz of the gas-lit streets. And so, I suppose it is no surprise that I set my own stories in such a world. After all, they say you should write what you love. And they also say you should write what you know - although what could I possibly know about life in the nineteenth century?

Well, I’d watched those films, and I'd also read a lot of Victorian fiction. I study a lot of history when researching the details for my books. But, more than that, I've always partly lived in a Victorian world. I still do today, and so do you.

I don't claim to be a time traveller, but I walk the same streets that my ancestors did. I visit the same pubs and theatres. I live inside their houses too. Even with modernisations, it’s not that hard to look around and imagine how things used to be ~ yet more so by having access to one of the greatest inventions of the nineteenth century which is the art of photography ~ which means that, unlike other eras from further back in history, we can actually see how those people looked, and the world that they existed in; only not in colour.

![]()

Here is a small selection of some of our oldest family snaps. I’m not sure who the old man on the right could be, though I love the way his terrier is so proudly displayed on a table cloth. And the one at the bottom, that’s Mum’s dad, looking as if he’s stepped straight out of the TV Show, Peaky Blinders. And then, there’s the one on the left who looks like Robbie Williams! So, perhaps there was some time travelling - and as William Fox Talbot, a pioneer of photography said, what photographs can give to us is: A little bit of magic realised.

I felt a little magic involved just before I wrote The Somnambulist when I went toa genuine music hall, with Wilton’s in East London still opening its doors to the public today; and still so full of atmosphere. You can almost smell the cigar smoke, hear the pop of champagne corks, the clatter and bang, the laughter and singing going on.

But there was another stage of sorts that inspired me years and years before, and that was introduced to me by my grandmother, Octavia Thomas, who was known as Betty to her friends. Whenever I went to visit, Betty would play her piano for me, singing lots of songs as well ~ just as my imaginary Cissy plays and sings for her niece, Phoebe Turner, in the pages of The Somnambulist...

When Betty first married my grandfather, Brian, she went to live on the top two floors of what had once been a coaching inn, at the bottom of Broad Street, in Leominster. The Inn, really quite a grand hotel, had been built in 1840. But, by 1851 the business failed ~ having opened up at just the wrong time, at the dawn of the railway era, and with very little going on in the 'old fashioned' coaching trade.

When I used to go there, during the 1960’s, the lower floors of Broad Street were used as a shop front. The rooms above were offices, and the rows of stables built behind provided ample storage space for the agricultural feed and machines in which my grandfather used to trade.

His father, my great grandfather, had worked in the very same premises. Before owning the property outright, in the late 1800's he became a partner in the firm of Alexander and Duncan. Back then, the company specialised in the sale of ironmongery.

What had originally been the ballroom (shown here from a newspaper advertisement around the time of its building) was used as a fancy showroom, filled with objects such as fire surrounds, tables, bed frames, umbrella stands. But by the time I knew the room it had fallen into disrepair. It was filled with machines and sacks of feed, and who knows how many rats and mice. But I loved to hear my grandmother describe the way it used to be, with music and dancing and lovely clothes. And I felt such a sense of wonder whenever I stood on that ballroom stage, surrounded by cracked plaster work, with the cobwebs draping down like lace, but feeling a sense of enchantment too while I dreamed of the glamour of its past.

And later on ... much later on, those feelings were still haunting me when I found myself in Wilton’s Hall and tried to imagine such a world through the eyes of Phoebe Turner, when she dreams of performing on that stage.

![]()

Another place that haunted me which appears in The Somnambulist, albeit in fictional disguise, was the grand construction, Hampton Court ~ what I’ve renamed as Dinwood Court. This picture is more or less as it looked when I was still a little girl, when I so vividly recall spending Sunday afternoons (those days when I wasn’t at home watching those black-and-white films on TV) sitting in the family car while we drove around the countryside. And whenever we went past Hampton Court I always hoped the car would slow, gazing out through the window to see the gates, and then the drive that led the way to what looked like a fairy tale castle. And then, when I was older, and back for the summer holidays after going to university, I had a temporary job working as a cleaner at the house. So, I finally got to look inside.

At that time the house was privately owned – I think by a transport tycoon, of whom I never knew that much: only that I had to use a Ewbank instead of a motorized hoover so as not to disturb the owner’s peace. It really was quite a task. There seemed to be miles and miles of red carpets running along the corridors ~ where I very often got quite spooked by the metal suits of armour that stood to attention on either side, just as I did in one of the bedrooms which had an eerie atmosphere, so cold and hostile that I really didn’t like to go inside. But, later on, when I wrote my book, I used the way I’d felt back then to conjure up some ghostly scenes that Phoebe Turner experiences.

Nowadays, with new owners who open the house for visitors, you can explore the gardens, even have a coffee or afternoon tea while sitting in the Orangery where Phoebe is first introduced to my fictional owner of the house: a woman called Lydia Samuels, for whom she will be a companion.

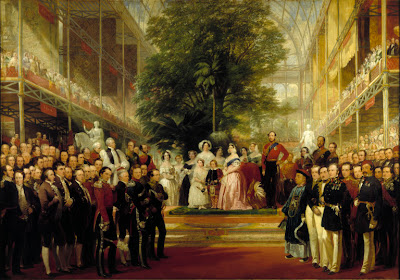

In reality, the orangery was designed by Joseph Paxton, famed for the Crystal Palace that housed the Great Exhibition of London in 1851. That setting is one that you will find if you read The Goddess and The Thief, but tonight we’ll be staying in herefordshire, and when it comes to Hampton Court, I feel so very privileged to have roamed around that house alone, before I would join the rest of the staff ~ other cleaners, gardeners, and handymen ~ when we ate a hearty three-course lunch around the kitchen table; with those lunches going on to inspire my own Victorian kitchen scenes taking place in The Somnambulist.

So often I embellished that short time I spent at Hampton Court when I started to write my novel. The story begins in London, but soon, having hit upon hard times, Phoebe travels by train to Herefordshire to take up her new employment. And when she arrives at the station it’s night, and she finds herself to be alone, as shown in this extract from the book -

I could hardly have felt more miserable. There I was half blind and abandoned in some god-forsaken country place which amounted to two narrow platforms and a rickety bridge in between. A creaking sign said Dinwood, and below that, the hands of a big round clock were pointing to after eleven o’clock.

I knocked at the ticket office door, which was locked, with no sign of any life. On the door next to that was a nameplate: The Dinwood Cider company ~ and behind barred windows were barrels and bottles, and some other slinking shapes that I feared could only be vermin. Pushing through a gate at the side I saw nothing but piles of logs and slag. I shouted ‘hello’ but my voice was drowned in the heavy beating of the rain. Much dejected, I went back to sit on my trunk, wondering what to do for the best – which is when I saw the light of a lantern, and the thin silhouette of an arm reaching out, impossibly long, with a hook at the end ... and having read all those sensational stories where young women were lost to cruel fates on dark nights, I became quite convinced that this was some lunatic monster set on a blood-crazed murdering spree.

But, when I opened my mouth to scream, a deep burring voice was asking me, “Is it Miss Turner ... Miss Turner come for Dinwood Court?

Raising a hand to my brow, shielding my eyes from the rain once more, I saw no monster standing there, only an old man in a drooping straw hat with a fringe of white hair plastered wet to his brow. His chin was hoary with stubble. His cheeks were threaded with purple veins, but his eyes were a clear and sparkling brown, looking friendly enough as I nervously said, “Yes... that’s me. Who are you?”

Well, the old man is Mr Meldicott, who’s been sent to collect her from Dinwood Court, after which Phoebe then finds herself ...

"...sitting in a rattling trap, a draughty flapping roof on top, and the road aglow with the lantern light, as were verges of grass, muddy ditches, and hedges, where the heads of white flowers were gleaming. The air smelled damp and mushroomy. Mr Meldicott whistled some popular tune, something Cissy once used to sing as well, though I couldn’t remember the name of it. His accompaniment was the clop of hooves, the splashing of big wooden wheels, the drip, drip, drip from branches above where trees on either side of the road formed a dark arching tunnel above our heads. From time to time he clicked his tongue, soothing the horse when it whinnied or shied as shadows danced around us ... while I shivered and yawned with exhaustion, and finally let my eyes droop closed ... only stirring again when we reached some gates which, being made of iron, very heavy, very large, made the most horrible clanking sound.

![]()

I saw the house loom up ahead. A central square tower above an arched entrance, castellated walls running either side, and so many windows ... I couldn’t even begin to count ~ and each one unlit and unwelcoming. But, as the moon’s face broke through fast-scudding clouds, I saw something else that quite took my breath, the thing that was lying behind it, spreading upwards and outwards for several miles: the dense, sloping woodlands that glistened like silver. And, being quite overawed by that, and sounding more like Old Riley than me, I exclaimed, “Strike a light! What a wonder. I’ve never seen so many trees in my life.”

Old Riley who Phoebe mentions there ~ well, she’s a theatrical dresser, who throws in a bit of palm reading too. A larger than life character with a role in most of the London scenes. But, in ways and looks she wasinspired by my great Aunt Hazel from Leominster, who once ran Dimarco’s fish shop, with her husband, my Uncle Eric. Just like Aunty Hazel, Old Riley only has one eye, having lost the other when a stone was thrown up by a vehicle in the street. I was always intrigued by that one eye ~ and yet, much like Old Riley, Aunty Hazel never missed a thing!

But back to those trees that Phoebe sees ~ what I describe is the Queen’s Wood, where I often wandered in my youth along with my mother, brother and sister. And when Phoebe also walks there I try to convey the mood of the place, and the way I felt about it – so mysterious and magical; like being in another world. And, it really is for Phoebe, who's never been out of London.

My skirts brushed against the damp grasses. Directly ahead trees were steaming with moisture, almost as if they were living and breathing. I hesitated, and it seemed that all nature’s sounds hesitated too, as if those woods sensed my arrival, the stranger who entered their dappled green gloom. My fingers scraped over rough bark of trees as I gazed up into the canopy where branches were woven so tightly together, where shafts of gold light filled the gaps in the green, where the wood was creaking as leaves weighed low, still heavy and dripping with jewels of rain. There was a stream – a waterfall – that splashed over boulders furred velvet with moss, and I stood in that verdant magical place and almost believed it was welcoming me, that the birds in the branches were singing my name. The prettiest: fee bee, fee bee.

![]()

And thinking of sounds of water brings me on to Elijah’s Mermaid; another novel that has been hugely inspired by Herefordshire. Again it has that London versus the countryside divide, which has been a defining part of my life, and which is also a common theme employed in Victorian novels where, in a broadly simplistic view, the country is often viewed as good, and the cities as scenes of disease and vice, where exotic and dangerous strangers roam.

What could be more exotic than a nymph, or a mermaid ~ and this painting by John William Waterhouse, which is called A Mermaid, takes me straight back to Leominster Library, when it was based in West Street, and looked a bit like this inside –

It had such a big influence on my life. I used to get so excited when I saw the little lender’s cards being placed in their folders in the tray; particularly when I borrowed the stories of fairy tales I loved ~ such as Hans Christian Anderson’s tragic tale of TheLittle Mermaid, or Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies, with both of those stories going on to inspire Elijah’s Mermaid; even if I reimagined them in a much more adult way.

![]()

Water played a big part in my childhood. I have such vivid memories of living in The Meadows, and then Cranes Lane in Leominster, with the fields behind both houses running down to the river, where we’d go for walks and family picnics ~ avoiding the cowpats on the way until we came to the sandy banks on the other side of an old stone bridge. We would paddle or swim in that river, or swing from the branches of willow trees. We would fish with jam jars held on strings to catch our tiddlers, or bully heads. And, in bed at night I’d go to sleep and dream of diving down under the water and living with the mermaids ...

![]()

But, as well as looking idyllic, water can be dangerous – just as it is in The Water Babies, when Tom, a little chimney sweep is drowned in a river while trying to wash away the soot that covers him ~ and through this fictional story, Charles Kingsley was also hoping to show just how cruel and exploitative were the laws in the nineteenth century when it came to child labour; when the virtue and glossy morality on the surface of Victorian life was unable to hide the stench of the sewers, and a seething underworld of sin.

![]()

When I wrote Elijah’s Mermaid I also tried to allude to that hypocrisy and sin ... starting with the story of Pearl, a girl who is found as a baby floating in the river Thames, where her unmarried mother has drowned herself, and means for her child to die as well. But, having been rescued that dark night, Pearl is then raised in a brothel, though her fate isn’t quite what you might think ~ becoming the muse of an artist, who is obsessed with her beauty, and who paints her as a mermaid.

The novel has two narrators. So, as well as Pearl in London, there is Lily and her twin brother, Elijah, who both grow up in Herefordshire, and their childhood is very different to hers, being raised by a kindly grandfather, who both the children called ‘Papa’ ~ and he writes Victorian fairy tales ~ and he lives in the village of Kingsland. And here, once again, my childhood played a part in the setting of those scenes.

As a little girl I came to know the village of Kingsland very well; often staying for days on end in the home of my aunt and uncle who ran the local post office, and who often took us children on walks through the countryside around. So, recalling those happy carefree times, I have my twins often spending hours beside a little stream that runs at the end of their garden, and roaming the fields by the village church; a place where I’ve always loved to walk, and still do when I’m at home with mum.

The house where Elijah and Lily live was once the village rectory, and it really was covered in ivy as it is in Elijah’s Mermaid, though I had to imagine the rooms inside, never having stepped foot beyond the door. I also reimagined the stream that runs at the garden's boundary, making it somewhat larger, and more overgrown with trees and ferns. A secret oasis of tranquil green where the children dip jam jars into the water, hoping tocatch, not fish like me ~ but a water babe, or a mermaid, who might have got lost when she leaves the sea; just as one in their grandfather's stories does.

Nowadays, that house is privately owned, but you can still walk the glebe field, and pass through the swinging iron gate that enters the village church yard, where some members of my family lie ~ as do Lily’s and Elijah’s. You can go inside the grey stone church, with the Volka chapel that I have also described within this book; and in there you’ll find the open tomb that used to intrigue me every time I went to church on Sundays ... in which the grown up Lily lies, posing as Ophelia, while her brother (an artist and photographer) asks to take her picture, as if she’s in a painting ~ which is something Victorian artists did, either as the reference to copy on their canvasses, or as works of art in their own right. And here, Lily describes that day when she posed as the drowned Ophelia.

![]()

I shivered in that cold dank tomb. I was doing my best to look mournful – and dead. Both of my eyes were tightly closed. Both of my hands were crossed at my breast, which was sheathed in the finest muslin cloth; an old dress from another attic trunk that had once belonged to our grandmother, wrapped up in paper, perfectly preserved, and fitting as if it was made for me. I wondered what age she had been when she wore it – if she had also been twenty years. When I’d asked Papa he could not recall. Papa was starting to forget... and that day I also tried to forget the story I’d heard of the Chapel tomb – saying that it once held the bones of a woman and newborn babe. But in one of his rambling sermons when I was still a little girl, the vicar had distinctly said that the tomb had never been used at all, but was what they call a ‘symbolic’ grave, a memorial for the Wars of the Roses when, in the battle of Mortimer’s Cross – in a field, no more than a mile away – over four thousand men were slain. It had been a time of great tragedy, but one of signs and wonders too. In those moments before the battle commenced, when all of the soldiers were praying to God to make their side victorious, the heavens began to glow with the light of not one, but several shining suns.

A ‘parhelion’ – that is the scientific term. A sun dog the more poetic. But then, being so very young, I imagined an actual dog in the sky, and only when walking back home with Papa, when I must have mentioned such a thing, did he throw back his head and laugh and say, ‘Now, Lily, that would be a sight to see! Such an occurrence is very rare ... but nothing to do with a real dog, and certainly not a miracle . . . whatever the vicar chooses to think. It happens when the air is cold and crystals of ice form in the clouds ... and when the sun shines through them, and if all the angles of light are just so, then the rays begin to diffract and spread, much as they do when a rainbow appears. Instead of seeing an arch in the sky those soldiers saw many coloured stars. They say that to see such things brings luck, and I dare say it did for the Yorkists that day – all those soldiers who their carried battle flags embroidered with symbols of the sun.’

Well, that really did happen at Mortimer’s Cross, and that’s how I seeded it into my plot. But not everything that I researched ended up in the pages of the book, and one event I wrote about, and then cut from my novel, I’d like to tell you about tonight.

Images from Kingsland Village Website

We might take trains for granted now, but they were revolutionary during the nineteenth century. As I mentioned earlier, they soon did for the Lion Coaching Inn. But, on the whole they really helped the local farms to prosper, transporting livestock and other goods to markets much further away than before. They also allowed many people who might never have travelled about before to visit cities and seaside towns; even to move away to work.

Today, I like to take the train whenever I come back home again, enjoying the chance to sit and read, or to view the lovely scenery. And so did Phoebe Turner in the story of The Somnambulist ~ and then, in Elijah’s Mermaid, young Lily and Elijah go travelling to London ~ a trip they are very excited about, even though their grandfather’s housekeeper believes, as so many did back then, that to travel at such rushing speeds would lead to a form of brain damage. A nose bleed at the very least!

![]()

But, disregarding the Victorian doom mongers, William Bateman-Hanbury, the Lord Lieutenant of Herefordshire, founded a local railway. It cost around £80,000 of which the initial investors would receive an annual dividend of 4% of the profits, after which the service line was leased to the Great Western Railway, becoming fully amalgamated in 1898. Bateman engaged the engineers, Thomas Brassey and William Field, to construct the tracks that ran between Leominster and Kington. I once walked the remains of that line when, along with my brother and cousins, we decided to run away from home, heading from Kingsland to Leominster ~ from where the first train was to run in the June of 1862.

![]()

Before that, at the very start of work, Lady Bateman wielded a silver spade to dig the first earth along the track that would eventually end up as being 13 miles and 25 chains long. There were stations at the villages of Titley, Marston Road, Pembridge and Kingsland (with a private stop at Shobdon Court which was where Lord Bateman used to live), though the timetables could be - informal– with trains sometimes halting mid-way on the tracks to deliver local groceries, even to collect fresh eggs.

At the grand opening day, on Tuesday, July 28th in 1857 there was a great deal of excitement. The event having been well-advertised in all the local papers, there were banners and bunting draped up at the stations and people dressed in their Sunday best to attend a celebration meal ~ though the party was at first delayed when the brand new engine (which was named Lord Bateman) broke down just outside Leominster.

But despite any tempers being frayed, and with many of those who’d had to wait ending up being damp and bedraggled when the clouds opened up to pour with rain, the guests were dry and warm again at Kington's Oxford Arms hotel, where the Rear Admiral, Sir Thomas Hastings CB, presided over three hundred guests who sat to eat in the banqueting room. Above them were banners that read: ‘Times Past’ - with pictures of coaches and horses; while those that said ‘Times Present’ showed the design of a modern passenger train. And, as to the celebration feast ~ well, just listen to this menu, for which I’ve found some images from Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, which I think will give you a good idea of how that banquet could have looked.

![]()

"1 boar’s head, 6 spiced beef, 4 roast beef, 6 galantines of veal, 10 forequarters of lamb, 20 couples of roast fowl, 6 couples béchamel fowl, 8 hams, 10 tongues, 8 raised pies, 12 turkey poulets, 28 lobsters, 12 lobster salads, 4 Savoy cakes, 8 Danzig cakes, 8 rock cakes, 8 plain cakes, 8 charlotte russe, 8 Polish gateaux, 8 Viennese cakes, 8 raspberry creams, 8 pineapple creams, 12 dishes of tartlets, 12 dishes of cheesecakes, 12 fancy pastries, pineapples, grapes and fruit, etc."

Goodness me, what a feast that must have been! But, sadly Times Present didn’t last, and although the train line carried freight and goods until 1964, it was closed for public travel from 1955, by then unable to compete with the more successful bus companies. The last train at Kington station found a black flag hanging to greet it, before the final return was made.

What a sad day that must have been.

This post forms the greater part of a talk prepared for the Herefordshire Libraries Book Festival.